Our Training and Campaigns Coordinator Bea, writes about why Children in Need is problematic today. Disabled children have the right to be included in their local community and to do the kinds of things that non-disabled children do. They have the right to support to help them do this. Following the ‘Rights not Charity’ chant of the Disabled People’s Movement, Bea explores the tensions with a ‘needism’ approach to Disabled children’s rights.

Why?

First of all, can I say I’m not (and never have been) opposed to charitable giving. To be charitable is to show compassion and empathy for those who suffer, or are in situations where life and limb are at risk. I am a child of the ‘Live Aid’ generation. I too have bought the Band Aid single and thought about the Ethiopian tragedy.

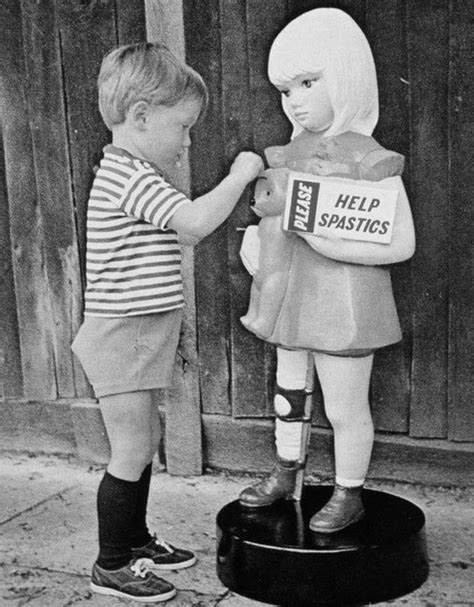

But I also thought: why? Why had starvation happened, and why was it happening with such regularity across the planet? When I was child, I remember Biafra. Or being at school and taught to think of the poor children of Africa. I was taught that giving was a good thing, and even though I came from a relatively poor family, that giving to the charitable campaigns that came up every so often was the right thing to do. Even when I took my pocket money to the local newsagent to satisfy my sugar craving (a weekly event), there was usually a plastic (or ‘boody’) figure of a poor little child wearing a caliper ready to accept any pennies I had left.

Charity as a system was baked into life, as inevitable as breathing. It was supported by the morality I had been taught. A Judaeo-Christian morality. It was right to give to the poor, the disabled, and those affected by disasters. But, “the poor will always be with you”, so it was said. And that meant that campaigns and giving were going to be a permanent feature of society. Our society in the UK, and other societies elsewhere, both poor and rich.

Still, the question ‘why?’ haunted me. Why was it that we, as a community with moral standards, couldn’t do something permanent about the serious problems that haunted the world around me? Each year, I saw the same man-made disasters occur, and hear the appeals for aid. Each year I saw the charitable campaigns for the disabled recur, and hear the appeals for donations. No one ever seems to have said why this was a recurrent fact of life. Or why the situation for minority groups across the world seemed to stay the same, no matter how many millions of pounds were raised. The poor (the disabled, the forgotten, the unpopular causes) were indeed still with us. No matter how many times I put pennies into the box that the plastic child was carrying.

Still, the question ‘why?’ haunted me. Why was it that we, as a community with moral standards, couldn’t do something permanent about the serious problems that haunted the world around me? Each year, I saw the same man-made disasters occur, and hear the appeals for aid. Each year I saw the charitable campaigns for the disabled recur, and hear the appeals for donations. No one ever seems to have said why this was a recurrent fact of life. Or why the situation for minority groups across the world seemed to stay the same, no matter how many millions of pounds were raised. The poor (the disabled, the forgotten, the unpopular causes) were indeed still with us. No matter how many times I put pennies into the box that the plastic child was carrying.

Philosophical Dilemma’s

When I grew up and began studying philosophy it became plain that there was an ethical dilemma at play. Here I was, a disabled person, someone who was ‘in need’ by definition of my bodily morphology. Hence I welcomed the voluntary actions of the non-disabled in ameliorating the issues affecting my life. What’s not to like? They were doing good. I was (and am) grateful. Organisation were created to help people like me, huge efforts put into play, voluntary hours given freely, and money raised by those who had never met me. It was heroic

So why did I feel so unhappy?

Not just because of the dependency, and resultant stigma, of being a charitable recipient. But also an awareness that we, as a society, were dealing with the surface issues of inequity, but incapable (or unwilling) to deal with the root causes.

The matter of modern charitable giving, at heart, relies on an embedded individualistic vision of societal obligations. It says that the individual is responsible for all the matters that affect them, and must deal with these without making onerous demands on others. This concept evolves from unchallenged (‘hegemonic’) attitudes we learn as we grow. One of these is that it is up to ME to deal with my disability. I should not expect other people to have an obligation to change their life-styles in my favour. Other than those motivated by any affectations they may have. By affectations, I mean common emotional responses, such as pity, sadness, sentiment, guilt, etc.

In response to such affectations, we give to charity. The affectation goes away once the giving has been completed. And how much better if we enjoy ourselves whilst we’re doing it! We can mollify those slightly Victorian feelings of charitable holiness by watching entertainment as we donate. In a sense, we receive something indirectly in return for giving, and hence can absolve ourselves of residual mawkishness. It’s easier to be a ‘quasi-Mother-Theresa’ if you’re watching your favourite singer or comedian giving of their time on TV. There’s less of that embarrassing moral uncertainty to worry about.

Why it’s problematic

It’s what I like to call ‘Children-in-Need-ism’. Every year the Children in Need charity marathon happens on TV. The organisers attempt to break the record raised across the UK each year. We give, or campaign, or sit in baths full of beans. We are sometimes even interviewed whilst giving. There are solemn moments when the benefits of last year’s fundraising are displayed. We may think: how lovely that these poor disabled kiddies (or elderly people, or Downs Syndrome children, or wheelchair users, or…) now have a better community centre, or bus, or can employ a fundraising worker. Just add your own recipients and outcome to this list.

Yet no one ever asks: why are there still children in need in the UK? In one of the five richest nations on earth, and a society that (at least in theory) says it cares deeply about the welfare of its youngest members. No matter how much is raised and disbursed, no matter how many heart strings are plucked, no matter how we feel we need to act to take away the sense of guilt and pity, the same old problems exist year to year. The names may change, but the issues stay the same.

As I said at the beginning, I am not in any way hostile to charitable giving. I am simply concerned about its futility in dealing with systemic matters of inequity and neglect. Please don’t let anything I have written above discourage you from giving to Children in Need, when it comes around. Or putting your loose change in a collection box. Such things do help, even if only peripherally. But when you do give, consider what could be done to permanently improve the situation for disabled people (and others) at a national and international level.

Then, ironically, we may work towards never requiring Children in Need again.

Bea Groves McDaniel, November 2023

Join us to help end discrimination of Disabled people in the North East.