By Debbie Austin, from North-East and Cumbria Learning Disability Network, talks about how the social model of disability helps her be a better parent.

Learning about the social model of disability changed my life. I was 25 and travelling in Australia occasionally working as a physio, and generally having a great year or so away.

In the height of the Australian summer, a friend and I were in a café in North New South Wales awaiting the opening of a festival. As we were preparing to leave two men came in and looked around for a table- I indicated that they could have ours and as they wheeled over, we said hi and started chatting. We were going to the same festival so lots to talk about. We bumped into each other at the festival and at the end of the weekend they gave me their number and said to look them up when I made it to Sydney.

(This video from Shape Arts is useful in explaining the Social Model and a good one to share with your colleagues, friends, family etc. to help them understand too.)

Fast forward 6 months and I find myself in Sydney looking for work and somewhere to stay. They offered me accommodation and over dinner night after night they spoke to me about their lives as disabled people, their schooling in 1960’s and 70’s Sydney and the treatment they experienced at the hands of professions like mine. I learned about the social model of disability, disability activism, the importance of language, and what makes a wheelchair responsive and easy to self-propel.

A Fundamental Truth

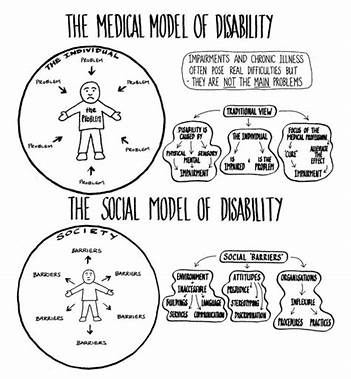

Hearing about the social model was like learning a fundamental truth- something so right that I knew it had changed me from that moment on. I woke up to the discrimination and objectification of disabled people and I was shocked, appalled, energised and motivated. The social model made perfect sense and I wanted to shout it from the rooftops. “Surely” I thought “when people hear about this, they will see what has to be done, it can all be put right because everything that needs to change can be changed- attitudes, opinions, policies, buildings etc etc”. This was 1995- I returned to the UK and found myself not only at odds with my profession, but surprisingly many people in society.

Fast forward to early 2008 when I was delighted to find I was pregnant. At 14 weeks I was offered an antenatal blood test for both Down syndrome and Spina Bifida. I was not naïve I knew these tests represented a desire to screen out. I had the test from a pragmatic position- my partner and I were moving in together each selling our home to buy one together. If we knew our baby may have mobility needs, it made sense to buy a bungalow.

The results came back, with wording that was negative- risk not chance. Our baby had a 1:6 risk of having Down Syndrome. 2 amniocentesis appointments were booked, indication clearly to us how important the hospital felt this was. My blood test posed no risk to my baby but the amniocentesis did. I declined both and continued my pregnancy advocating for my baby. It was just another unknown- and there are countless when a new life in on its way. We don’t know if our baby is a boy or a girl, we don’t know if our baby has Down Syndrome or not, etc etc etc

Lucy was born with Down syndrome in September 2008. I am eternally grateful I knew about the social model of disability because I didn’t grieve the baby I had never had, (as I was told I would/should). I celebrated and welcomed her. I wasn’t shocked I was totally in love. I remember thinking that surely there wasn’t a name in existence beautiful enough for her.

Inconsistencies and Attitudes

This knowledge and fundamental belief that she was perfect as she was, allowed me to deal with the questions that followed. “Did you know, didn’t you have the test?” questions to which I replied yes and no.

The social model enabled me to see and, importantly, believe that all the issues we encountered were external to her. They were to do with the flaws, inconsistencies and attitudes in our society and system- she was perfect at just being Lucy.

As Lucy grew, we started to see behaviours that we found difficult- these began at around the same time as the scandal at Winterbourne view was exposed and continued as she grew. I was terrified- and fell into medical model thinking about Lucy’s behaviour. “How do I get you to stop?” I wanted her to stop because I was so scared of what people might do to her if I didn’t “get it under control”.

Amongst other things Lucy was hitting me a lot- often when I was putting her shoes on as we were getting ready for school. I didn’t know what to do, so I kept trying to teach her about kind hands. I had kind hands cards and stickers to show her, and I had kind hands stories to read to her, I praised her every time she used kind hands and I tried to ignore the hitting. Nothing worked- so I tried harder, more, louder… still no change.

I called our learning disability nurse and what she said was the start of a fundamental change in my parenting. She said:

- “Debbie, I have absolutely no doubt that Lucy knows what kind hands are- that’s not the point, she is trying to tell you something.”

I had never considered her behaviour in that way, although it seems obvious now. That conversation helped me to see that Lucy’s behaviours were her best and only way of communicating to me that something wasn’t right, that she needed something. So

- “How do I stop you?” became “How do I help you?”

I started asking around- “What could this behaviour mean- what is Lucy trying to tell me?” A chance conversation with a Teaching Assistant at school proved to be enlightening. I asked her if she thought the hitting, taking off people’s glasses and pulling hair meant that Lucy wanted some space, that she was overwhelmed a “leave me alone” message. “No” came the reply “it seems to happen when I am working with Lucy, and someone interrupts me” so it seemed to be the opposite- Lucy was saying “don’t ignore me”.

I thought back to mornings at home, a very busy time in many households, and wondered if Lucy was being unintentionally ignored. I spoke to my family and suggested that if someone asks me something when I am with Lucy, I will give a little squeak to say I have heard you but won’t reply until I have finished doing whatever I am doing with her. We agreed, the next morning when I was putting her shoes on, someone called me, I squeaked but kept my focus on Lucy. When her shoes were on, I gave her something to play with while I went to see what was needed and realised that she hadn’t hit me- and she never hit me again- in that context.

Social Model as life changing

It was life changing for all of us. All of Lucy’s behaviours that I previously thought were challenging were her simply doing her best to communicate that she needed something. So, by giving her what she needed stopped the behaviours. I have become skilled at reading her nonverbal and verbal cues of contentment and distress which show me when a need might be there and allowing me to put strategies in place to meet the need before she had to tell me with her behaviour. She is happier, we are all happier, and life ifs fuller and richer.

It was life changing for all of us. All of Lucy’s behaviours that I previously thought were challenging were her simply doing her best to communicate that she needed something. So, by giving her what she needed stopped the behaviours. I have become skilled at reading her nonverbal and verbal cues of contentment and distress which show me when a need might be there and allowing me to put strategies in place to meet the need before she had to tell me with her behaviour. She is happier, we are all happier, and life ifs fuller and richer.

Everything Lucy does makes sense when seen from her point of view. I stopped blaming her for the behaviours- something I didn’t realise I was doing until I stopped and tried to understand the world from her point of view. I stopped expecting her to change and realised that I had to change the way I parented her.

This approach fitted so neatly into my values around the social model of disability- Lucy behaviours I found challenging were not something to blame her for but were simply her way of expressing that she needed something, that something in her environment wasn’t right.

I am forever grateful to my friends in Australia for teaching me about the social model of disability and for everyone who has taught me since, especially my darling girl Lucy.

Debbie Austin

Strategic Learning Disability Workforce Development Manager-Family carers.

North-East and Cumbria Learning Disability Network.

20/02/24

Want to make the North East a better more equitable place for Disabled people? Join us as a member to keep up to date and get involved, if you want to/can.